Mental health requires meaning, not comfort

One of the paradoxes of mental health is that seeking greater comfort in life seems to result in less satisfying psychological outcomes, rather than more.

The psychological theories of the early Industrial Revolution were dominated by the idea that human behavior can be shaped by consistent rewards and punishments. While such theories are convenient for manipulating factory workers, their effectiveness is unreliable.

In Drive (Pink 2009), Daniel Pink wrote about what really motivates workers, and it isn’t money. After their basic needs are secure, most workers are motivated by:

autonomy (freedom from control),

mastery (self-efficiacy), and

meaning (a sense of belonging to a mission greater than themselves).

That means the greatest achievement of what American psychologist BF Skinner called operant conditioning was probably teaching pigeons to play ping-pong.

While incentive structures do help shape behavior, by the time American psychologist Abraham Maslow published his famous theory of human motivation (Maslow 1943), it was obvious that human beings are more complex than laboratory pigeons. Maslow, who began his career as a sex researcher after working as a doctoral student under the supervision of Harry Harlow at University of Wisconsin, recognized human drives as multifaceted.

All three of Pink’s human drives are present in Maslow’s famous work on human motivations, which Maslow organized in a hierarchy. At the bottom were basic needs like safety, shelter, and pleasure. According to Maslow, after those were satisfied, a thirst for power, a sense of belonging, social status could emerge. Finally, Maslow postulated that the highest calling of humankind was something called “self-actualization” — a striving to realize our fullest human potential. Although Maslow’s original formulation for the hierarchy postulated the most basic (safety, pleasure) must be satisfied before more complex motives can be realized, it wasn’t long before that linear ordering was discredited.

At the time of Maslow’s original publication, Austrian psychologist Viktor Frankl was imprisoned in Nazi death camps. After liberation, three years after Maslow’s publication, Frankl chronicled his experiences in Man’s Search for Meaning (Frankl 1946).

Rather than drawing on the autistic philosophies that enabled industrialization, Frankl built on the prior work of German philosopher Frederick Nietzsche, who wrote “He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how.”

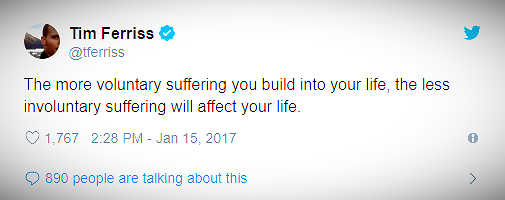

Frankl’s experiences helped him realized that neither pleasure nor power represent the purpose of life. That is, our psychological state cannot be improved by eliminating suffering from our lives, but instead by giving meaning to the suffering.

“The primary motivation for living is to find meaning." - Viktor Frankl

The pyschological risk of comfort

In the The Coddling of the American Mind (Haidt & Lukianoff 2018) college professors Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff bemoan the decline of the American University into a morass of comfortable lies and trigger warnings. In The 9 Cognitive Distortions Taught in College, I summarized the fallacies and misconceptions being taught in modern classrooms as I understood them from their book and my own experiences as a University Professor. They include:

emotional reasoning — confusing subjective feelings for objective reality.

catastrophizing — extrapolating setbacks into a disastrous imagined future.

overgeneralizing — confusing an example with some greater Truth.

all-or-nothing thinking — also called splitting, or black-and-white thinking.

mind reading — the belief that we have special insight into other’s thoughts, feelings, or motives.

labeling — ignoring exceptions to overgeneralized rules.

negative filtering — amplifying negative signals.

discounting positives — ignoring positive signals.

blaming and scapegoating — i.e., overlooking our own agency.

According to Lukianoff’s personal account of his recovery from depression, these cognitive distortions offer some short-term emotional succor at the expense of longer-term mental health. It was only by learning new patterns of thinking through cognitive behavioral therapy that Lukianoff was able to overcome them.

Ice bath psychology

There is no greater practical application of psychology than marketing. By mastering the complexities of human motivation, marketing geniuses seek to persuade us to make purchases, vote for favored politicians, or even support wars on distant continents. In his semi-autobiographical book on what works well in marketing, Oglivy & Mather executive Rory Sutherland writes that marketing “is not logical. It is psycho-logical” (Alchemy, Sutherland 2019).

In that pithy phrase, Sutherland contrasts the “conventional wisdom” (The Affluent Society, Galbraith 1958) that espouses the pleasure principle of operant conditioning with the reality of more complex human motivations.

Which bring us to the psycho-logic of the ice bath.

Why would anyone submerge themselves up their neck in freezing cold water for two minutes or more?

Like exercise, deliberate cold exposure is a systemic, hormetic stressor that stimulates the body to grow and strengthen physiologically and psychologically in response to stress. Unlike exercise, which is typically uncomfortable and exhausting, immersion in freezing cold can be painful, even when it is endured for just a few minutes.

Upon contact with the freezing water, thermoreceptors in the skin signal the amygdala to initiate a fight-or-flight response in sympathetic nervous system (Kanosue et al. 2002). This is the same response that is responsible for panic, and from an evolutionary perspective it causes a rush of hormones, neurotransmitters, and cardiac activation that prepares our body for life-saving action.

But something strange happens in the ice bath…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Self-Actual Engineering to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.