Preface

This week in my Startup School I assigned my students to read Seth Godin’s This is Marketing in which Godin writes:

All effective marketing makes a promise.

That turned out to be a problem for on of my students. They’re divorced, feel betrayed by their ex-spouse and ex-employees, and those feelings create an powerful instinct in them to protect themselves from criticism, manipulative acussations, and emotional flashbacks to those times when it felt like the exploitative assholes from their past broke promises to them.

And that’s a serious impediment to growing her venture, because Godin is right.

When you fail to make marketing promises, you're choosing to value your feelings more than the growth of your venture or the delighted customers who will benefit.

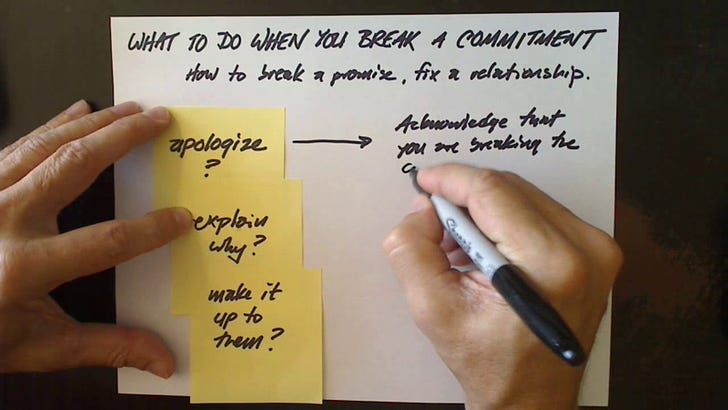

So I referred her to my article 'What to Do When You Break A Commitment,' because maybe knowing how to break a commitment will increase her confidence that it's OK to make promises. After all, if you know how to break them, then you needn't worry so much about making them, right?

What to do when you break a commitment

Once upon a time, I broke a promise. I had my good reasons, and I was choosing to break it. That is, I knew I was breaking my promise… even though the person to whom I had made this promise was very angry with me (and I would have rather that they weren’t).

That’s when I realized that she was still stuck in the “Apologize and make it up to them” protocol for breaking a commitment. And it reminded me that there’s another article about apologies that I haven’t yet shared on substack, so I’m publishing it now.

Apologies are not for the aggrieved

There are at least three different types of apologies:

Sympathetic,

Manipulative, and

To communicate intent.

All of these apologies are self-interested in the sense that they exist to help manage our own feelings. In some cases, they may ameliorate the hurt feelings of the aggrieved, too — but to ignore the selfish motivations that tempt us to offer these apologies is dangerous. Too many apologies are disingenuous in the sense that they provide for us a shortcut to moral satisfaction before we do the difficult work of self-examination.

Sympathetic apologies

The first kind of apology is supposed to communicate sympathy. It’s the one I used when I was traveling as a foreigner on a strange continent when I got a call from a protege who said, “I’m at the hospital. My best friend from college just died of septic shock after giving birth to her first child.

“I never got to tell her I love her. The last time we spoke, I was mad at her.

“Her family doesn’t know me and I don’t share their strict religious beliefs and I don’t know what to do.”

If you’re like me, the first thing out of your mouth is going to be, “I’m so sorry.”

But what am I sorry for?

I’m sorry I’m not there to bake a lasagna and listen to how goddamn difficult it is to grieve for a best friend when everyone around you is worried about the deceased’s fiance, baby, parents, siblings, and everyone else in the whole world except you, even though you hurt, too.

I’m sorry I can’t tuck you in when you’re so exhausted you can’t cry anymore. I’m sorry I’m on another continent when your parents and your boyfriend are useless to you because there were always things about your freindship you couldn’t share with them.

I’m sorry I’m as useless to you as them right now.

Sometimes I’m sorry for myself.

So, even though it can be comforting to the grieving to hear “I’m sorry,” as an expression of caring, support, or love, it’s only what we offer when we have nothing else more meaningful to give.

Manipulative apologies

The second kind of apology is the type our kindergarten teachers forced us to say when we broke our classmate’s crayons or something, and it is entirely self-serving.

This type of apology sometimes comes out like, “I’m sorry if you…” or “I’m sorry but… .”

“If,” and “but” apologists are only sorry they aren’t getting away with it.

There are no ifs or buts in an apology. These conjunctions erase the apology and turn blame back on the person who was harmed.

This is the type of non-apology that is only offered as an immoral manipulation. The person offering phrases like these has perverted the apology to their own ends, exactly the way that their kindergarten teacher taught them… as if “I’m sorry,” was some sort of magical Get Out of Jail Free card.

When I used to get this type of apology from my kids, in exactly the way their teachers taught them, I answered, “Don’t apologize until you’ve fixed it.”

The Intent Apology

Which brings us to the third kind of apology — when it really is our fault, and we’re largely powerless to fix it.

This type of apology relies more on empathy than it does on sympathy, and it behooves us to explore how.

Consider what’s going on in the mind of the aggrieved party. When you’ve harmed them, and you’re unwilling or unable to fix it, they will make a moral judgment of your character, because they need to decide to what extent they will rely on your conduct in the future.

When making such a judgment of character, they must decide how much to weigh your intentions. They’re already aware of the outcome and they’re not happy about it. But they know (as we all do) that no one has control over outcomes. Randomness, complexity, and things outside our control intervene between our intentions and the resulting outcomes.

It would be wrong to hold anyone morally accountable for things that are outside their control, and so the aggrieved must make a determination of your character based on more than just the outcome of your actions. They must judge your intent.

However, intent can never be known with certainty. For goodness sake, we’re often ignorant of our own intentions. By comparison, the challenge of discerning other’s intentions is doubly difficult.

So it may be that the aggrieved judges your intentions by the apologetic story you tell them about what you did intend and the fact that you offer an apology. In this respect, apologies are unreliable, because the aggrieved must distinguish between the second (selfish and insincere) and third (attempting to be helpful to repair a relationship) kinds.

When offering an apology of the third kind, remember that the aggrieved party may be traumatized by more than the harmful outcome. In addition to whatever damages have been inflicted, they may feel betrayed.

One thing that I’ve found helpful both for their feelings and for my own is to describe in detail the action I regret and what I would do differently if I were faced with the same choice again. The act of making my regret specific, and telling the story of what I would do differently is consistent with the steps in What To Do When You Break A Commitment:

Admit you’re breaking the commitment,

Acknowledge the impact that breaking your commitment has had on the aggrieved, and

Explain what new commitment you are willing to make.

For example, it might sound like, “I regret that I didn’t return your hand tools when I promised. That must have been aggravating to not have them when you were planning to finish the shelving in your garage over the weekend. If I could do it over, I’d call you and tell you that I broke your saw, and that the replacement won’t arrive for three more days.”

Although this story doesn’t rewrite history or change the present, it does give the listener more confidence that my intentions were true to their needs, at least as far I understood them. The last step, retelling the story of what I would do is essential, because even though it’s only a story, the feelings the listener experiences when they hear it will help replace some of their greivances.

In this way, the apology may ameliorate feelings of betrayal — but, it might not.

It is not the aggrieved party’s job to caretake for my feelings. They have no opbligation to accept or acknowledge my apology, nor protect me from sharing in the adverse consequences of how I harmed them, because deep-down you are apoligizing for me.

What works for me?

I never offer the manipulative apology. It’s selfish and disingenuous.

Sometimes, I will offer the symapthetic apology. Although I admit that this is also selfish in a way, it is not disingenuous. I wish I was a better, stronger, more helpful person to those that reach out to me. I’m sorry (for myself, and for them, too) that I’m not the superhero I aspire to be.

I do offer the intent apology — maybe too often. The fact is I screw up, and it sucks and sometimes, when I’ve done the difficult work of examining my decisions and my behavior and I’ve figured out what I regret and how I would do things differently if I could… well, that seems like a good time to offer an apology.

Why not apologize?

Because an apology without a remedy, or a new commitment, or an honest appraisal of intention may feel more like a manipulation than an attempt at relationship repair.

That’s a confusion I seek to avoid.

Post-script: Marketing Promises

Godin asks his reader to empathize with their customers when making marketing promises. That is, he suggests that the best marketing is the type that is motivated by solving problems for customers, rather than for yourself. What’s more, Godin writes that most people are motivated not by techonologies, or product features, or even price, but by the feelings they get when they become your customer.

That puts you in the difficult position of making a marketing promise that is out of your control. Because you can’t promise that people are going to feel a certain way, how can you possibly make a marketing promise that is predicated on an expectation of their feelings?

Well… think forward a little bit to what you can commit to if it turns out your customers feel different from the promise that you made them.

In that case, you don’t apologize.

You offer them their money back, and you thank your lucky stars that they will never be your customer again.

Sometimes, whatever it is you’re selling just isn’t for everyone, and there’s no harm in finding that out after they try it.

Additional Reading

How to make better decisions.

Years ago, before I co-founded Morozko Forge, I was in a meeting that devolved into a debate about which software platform we should use to develop a custom tool for our most important group of clients. I recommended a platform that was particularly well-suited to the job, but our lead programmer didn’t have experience with it. He advocated for a plat…