What to do When You’re in Emotional Flashback — 4 Steps

And how to help others struggling with Complex PTSD

Pete Walker wrote an amazing book called Complex PTSD (2013) in which he described a form of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that results from chronic, rather than acute, trauma. Unlike the more familiar PTSD, which can occur as the result of a single incident, C-PTSD results from extended periods of abuse, neglect, or exploitation from which there is no escape.

Kayli Kunkel provides a concise description:

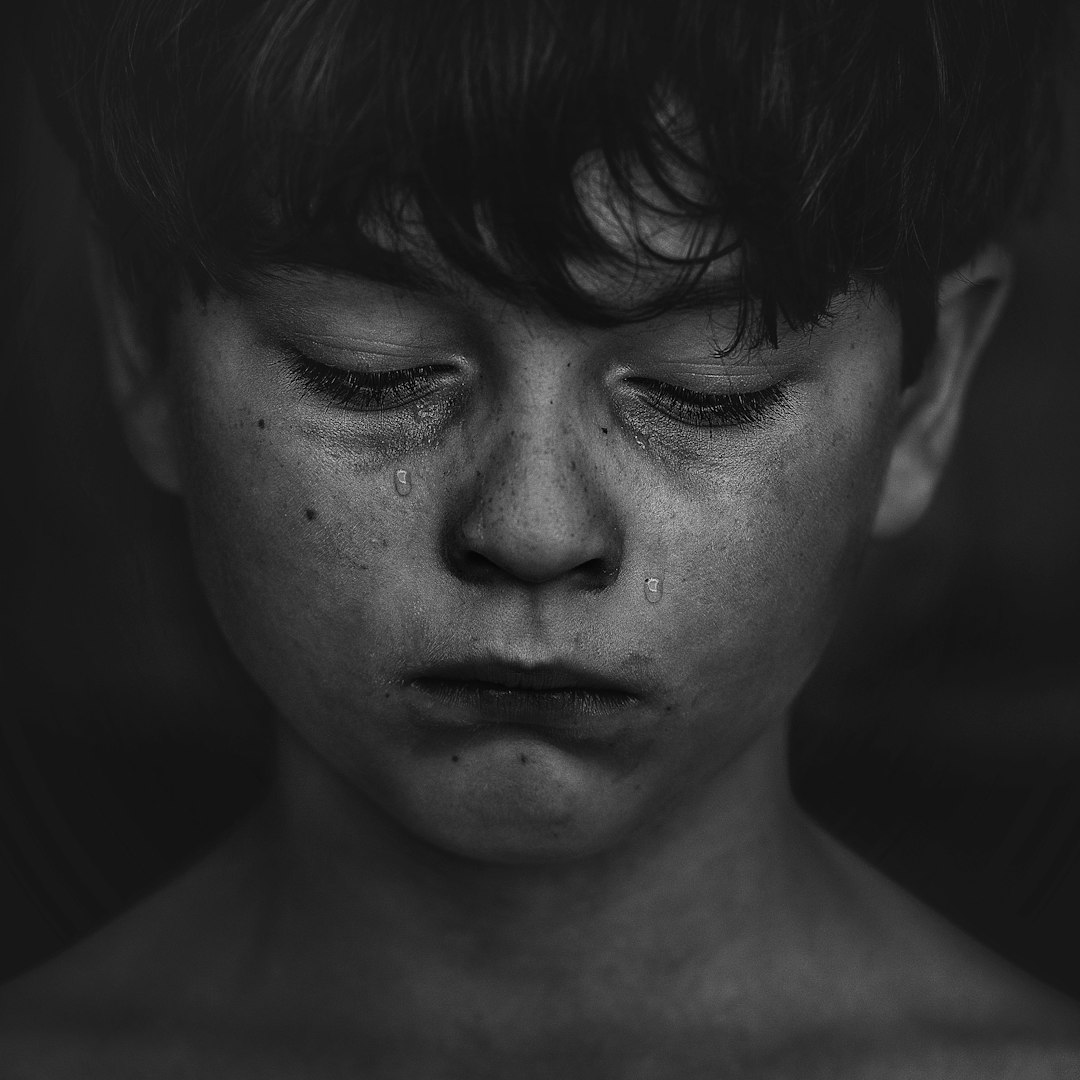

C-PTSD is a crippling but often misdiagnosed condition. It occurs when a person faces many traumatic events in an ongoing manner. This often happens in childhood, when children are exposed to some combination of sexual or physical abuse, emotional or physical neglect, warring parents or consistent instability and change.

These children often form insecure attachments with caregivers and have no outlet for their pain. So for survival, they develop traits like excessive reliance or independence, buried emotions, and mistrust as a general approach to relationships. They often disbelieve their own capabilities and do not feel like they can overcome the repetitive shackles of their past, even though those event patterns did not reflect them at all.

—

Although children are most at risk, the symptoms of the syndrome may not manifest until adolescence or early adulthood. When left unresolved, a person with C-PTSD can carry their trauma with them throughout their entire adulthood. For example, I wrote about one woman’s struggle with C-PTSD in ‘The Empathetic Post-Love Love Letter’ after we had broken up.

Then, in ‘Gifted Children Deny Their Emotions to Please Their Parents’ I described the necessity of emotional self-expression for healing from childhood trauma, and the difficulties in adulthood expressing emotions we learned to suppress as children. It is this connection between our present day adulthood and out past chilhood trauma that is a characteristic feature of C-PTSD and it is called an emotional flashback,

The Intuitive Therapist writes that emotional flashbacks can wreck your relationship.

I can relate.

Because all relationships with good “chemistry” will have their emotional trigger points with origins in trauma, I’ve started thinking about what we can learn from emotional flashbacks, and how you can help when someone you love is suffering from them.

Understanding Emotional Flashbacks

According to Walker, an emotional flashback occurs when an adult is experiencing emotions in the present moment that are the result of previous trauma. A.J. Kay described it well in her 2018 article ‘Run Girl Run’ (that has since been censored by Medium).

My thoughts raced toward the inevitability of abandonment like a landslide, through a rut in my brain that developed long before I knew what a brain was: an unnatural neural pathway, connections soldered together by neglect and self-loathing.

Next came the rubberneck of negative emotions choking out all rational thought: terror, anger, pain so deep I grasped at my chest. They were alive: a rat king, bound and sick, pulling in different directions, re-opening scars with dirty, deformed claws — shredding my heart in real-time. I felt them pulling me apart — being dismembered.

He will leave me so I will leave first.

- A.J. Kay, ‘Run Girl Run’ (2018)

During an emotional flashback the nervous system becomes overwhelmed by a sense of existential threat that calls upon the sufferer to either Fight, Flight, Freeze, or Fawn. Thus, A.J.’s metaphorical “run” may in fact be a literal Flight response that would have served her well during prior trauma experiences from her childhood.

According to Peter Levine (An Unspoken Voice, 2010), had A.J. been able to act on her Flight impulse at the time of her original traumas, she might have emerged from the stressful experience without PTSD, because what Levine calls “immobilization” is a critical factor in the formation of trauma. Part of what makes children so vulnerable to C-PTSD is the fact that they can rarely run away. Being too small to Fight, clever children learn to protect themselves from trauma by mastering Fawn and Freeze responses that later leave them feeling ashamed that they were unable to fight back or run away from their persecutors.

In adulthood, when in the throes of emotional flashback, thoughts, feelings, and perceptions become detached from the reality of the present moment, and instead become dominated by the previous trauma experience.

When adults act out the stress response that was denied them as children, grown-up C-PTSD sufferers too often make their present experience worse instead of better.

How to Gain From Emotional Flashbacks

It may be helpful to know that emotional flashbacks can serve two useful purposes:

They may offer some protection from situations that have been threatening or traumatizing in the past by activating autonomic nervous system responses (fight, flight, freeze, or fawn) that might help us cope with threats. In this case, the flashback is a warning from some unresolved trauma in the brain that signals danger. The warning may be false, because the circumstances that are threatening and traumatizing to us as children might be trivial when encountered as adults — but our unresolved trauma doesn’t know that. So we act out (in our adult bodies) in defensive and self-protective ways that were may have been prohibited to us as children. In the throes of emotional flashback, we might cry, scream, lash out, run away, or make false accusations that seem to us very real, because they were probably true during some past traumatizing experience. In this sense, the emotional flashback might be a disproportionate, hypervigilant, response to some legitimate threat signal.

The emotional flashback may be the brain’s unconscious attempt to resolve the trauma by reliving it from a position of control. In The Genetic Self: Epigenetic (How your past is written in your DNA) I wrote about how traumatic experiences can modify gene expression to create automatic reactions to the triggers that signaled the trauma. Both the unresolved traumatic experience, and the emotional flashback are characterized by loss of control that amplifies anxiety. An emotional flashback may be the brain’s attempt to recreate the circumstances of the traumatic event, and replay it over and over from a position of control until a satisfactory resolution is acheived by successful practice. When we master roles, conversations, or situations through such practice, we gain confidence that we can apply the skills we've learned to real challenges. In this way, the virtual experience of the emotional flashback can serve as both a proving ground for testing and building skills that retsore a sense of confidence, self-efficacy, and control to the situations that threaten us.

In his book, Walker provides a list of 13 steps he recommends to help his clients manage their emotional flashbacks. In my own experience, I’ve found Walker’s recommendations are helpful for managing the emergency, but do little to prevent future flashbacks. For example, Walker recommends “Deconstruct eternity thinking: in childhood, fear and abandonment felt endless — a safer future was unimaginable. Remember the flashback will pass as it has many times before.”

While this is excellent advice for avoiding the catastrophic all-or-nothing thinking that Greg Lukianoff identifies as a common cognitive distortion (The Coddling of the American Mind, 2018), resolution of the trauma requires a deeper understanding its origins. Reminding yourself that your flashback “will pass, as it has many times before” does little to suggest approaches to ensure that it never happens again.

Besser van der Kolk (The Body Keeps the Score, van der Kolk, 2014) writes that we have a compulsion to relive our trauma from a position of control, in an effort to resolve it. That suggests that our emotional flashbacks will keep recurring until we discover their purpose and fulfill it.

With that in mind, I offer these 4 steps to learning from emotional flashbacks that have worked well for me.

Step 1. Acknowledge the emotional flashback.

It isn’t always easy to know that the emotions you are experiencing right now are the residue of traumatic experiences you had as a child, but there are clues. You may have fleeting memories of the experience, or you might feel small or childlike or helpless during the flashback.

It is often possible to pause in mid-flashback to ask yourself the question, “Is this a flashback?”

I know one woman who is getting better at identifying her own emotional flashbacks. She told me:

The thing that helps me most is asking myself if what I am feeling is proportionate to the bad thing that happened. Sometimes I can’t even identify a bad thing happening!

One way I check for proportionality is to imagine if someone else reacted this way to a similar situation, and ask myself “Would it seem reasonable? Or would I be annoyed by someone else acting this way?”

The annoyance, particularly, is a red flag because the things that irritate us most about other people are flaws we recognize in ourselves.

So pulling back and checking for proportionality and annoyance works well for me.

What I see in her description is an effort to step outside her flashback for a moment, in an attempt to see herself from another perspective.

I wish I had such a capacity.

For me, the answer is “Yes, I am experiencing a flashback,” when I feel the impulse to throw a tantrum. It took me decades to discover that as a child, tantrums were the solution to my narcissistic Father’s exploitation and neglect. As an adult, I couldn’t for the longest time understand why my tantrums weren’t being interpreted as the same desperate appeal for attention that helped solve my problems with my Father. Needless to say, my Lovers were threatened and confused. Now, I’m better at recognizing that my urge to tantrum is a good sign that I’m experiencing a flashback.

Step 2. Identify past experiences of the flashback feelings.

When we’re attuned to the fact that we are in a flashback, it becomes easier to remember the salient experiences that formed our trauma. For example, I was recently reminded of the time my Father had promised to pick me up after school to take me to my orthodontics appointment.

He was chronically late, which meant that I was faced with the choice of waiting for him at my dangerous inner-city school, or begin a walk home in the hope that I might see his car driving down the road, coming late to get me.

I walked, every time.

I don’t know why I have this memory, except that it left me with the feeling that I was alone in a dangerous world with no protection, no safety, and no one on whom I could rely. That was a common feeling for me, and it was often true.

However, it was a childhood experience. As an adult, I’ve learned to cope — perhaps even over compensate — for the feelings of abandonment I retain from my Father’s tardiness by telling my friends, students, and colleagues, “Take your time. There’s no such thing as late with me.”

It’s a way of reassuring myself that I have extensive resources at my command, I am in control of my own time, and no one has the power to waste it but me.

Step 3. Respond to the question, “What problem was I confronted with as a child that might have created these flashback feelings?”

The feelings we experience in an emotional flashback have their origins in past trauma. In ‘Your Past Is Written In Your Body’ I described how Adlerian psychology treats emotional expression as an attempt to solve an interpersonal problem. According to Adler, emotions are fabricated to elicit or compel behaviors from other people.

Despite Adler’s exaggeration, not all emotions are about interpersonal problems. There are some emotions hard-wired by evolutionary biology into our psychology, like disgust for blood or feces, that protect us from danger (Haidt, The Righteous Mind 2012). As human beings, we have emotional instincts that confer survival advantages, and some of them relate to relationships and others don’t. Whether an emotional performance is fabricated outrage, crocodile tears, feigned joy, or the instinctive cry of a hungry newborn baby is irrelevant. Adler’s point that emotional expression is designed to solve problems is a powerful insight.

As children, we are creative, resourceful, and ingenious. So we find solutions to our interpersonal problems, despite the fact that for much of our young lives we are at the mercy of adults much larger, smarter, and stronger than us. For example, too many children are prohibited from expressing anger. Although it’s quite normal for us to feel angry when our boundaries or sense of fairness is violated, many children learn that their parents will not approve of an angry child— especially when that anger is directed at the parent. An ingenious, resourceful child will learn to suppress that anger, perhaps by turning it inward, for fear of losing their parent’s love.

An emotional flashback is an experience of intense emotion that may help us discover the nature of a past trauma. Step 3 encourages us to explore the problems we faced as children for which our intense emotional experience might be a solution.

I know one young woman who suffers episodic flashbacks of acute shame associated with the perception of herself as “an incompetent, worthless, piece of shit.” Her feelings of inadequacy are so serious that the most mundane tasks can seem insurmountable obstacles, even though she is in all other respects a woman of outstanding intelligence.

One way of interpreting her overwhelming feelings of helplessness is that her emotional expression is designed to elicit rescue behaviors from her Mother. For example, when she is not in the company of her Mother, she does not emote in the same way. She is more stoic, measured, and capable. It is principally in her Mother’s company that she devolves into a gelatinous pool of tears over seemingly simple tasks like opening a can of cat food.

However, Step 3 challenges her to go deeper into the traumatic origins of her flashback. In her case, she experienced a profound sense of abandonment as a child of 6 or 7 years old, when her paternal uncle committed suicide and her Father left the family household to grieve. As the oldest child, she felt the performance pressure of minimizing her own emotional needs in the service of her parents, while her Mother was preoccupied with caring for her two younger siblings and processing her own anxiety and grief.

As a young child, she could not possibly have been the savior her family needed at the time. Her misplaced expectations of herself had no remedy, although she was smart and self-reflective enough to be aware of her own inadequacies. Her self-critical flashbacks are not realistic assessments of her own limitations as a young adult, but instead they are self recriminations for her failure to save her family from the despair experienced while she was emotionally neglected by parents overwhelmed with more urgent demands.

It’s no wonder she breaks down in front of her Mother to elicit maternal support. As an adult in an emotional flashback, she reverts to the repressed emotional state of abandonment and helplessness she felt as a much younger child. Had she been able to cry out then, when she was 6 or 7, and receive the attention and support she needed, she may not be traumatized nor experience the emotional flashbacks she has now.

Step 4. Decide What Problem You Really Want to Solve

Once you’ve identified the problem you experienced in your past that created the emotions you are experiencing now, you have the opportunity to choose whether that’s really the problem you want to be working on right now.

It may be that resolution of past trauma is an urgent, present moment agenda. But it doesn’t have to be.

Many times, the challenge we’re facing in the present moment that triggered the emotional flashback is not the problem we would choose to work on right away. In those moments, it is helpful to remind yourself that the epic argument you were about to have with your spouse will not address the problem you are trying to solve right now.

In those moments, it’s helpful to decide that you are working on a different problem right now, and apply your efforts towards that.

The difficulty with that is most people get so preoccupied with whatever solution they’re fixated on, that they lose track of the problem — especially when that solution involves using emotional expression to control another person’s behavior. Step 4 is intended to refocus the flashbacker on the things they remember they wanted to accomplish before they entered their flashback, and decide whether their current efforts are better directed towards their original intentions.

Helping Loved Ones

The protocol above shares Steps 1, and Step 12 with Walker, and adds the Step 3 about figuring out what problem the feelings solved as a child, so that the flashbacker can create more effective resolutions. What Walker doesn’t offer is advice for those who love the person suffering from C-PTSD.

Because the flashbacker is not having the same conversation or experience as their partner, witnessing a loved one’s flashback will create confusion and pain. The flashbacker is likely to project emotions on to their partner that would better be directed at those who traumatized them in the past.

Because this misdirected emotional projection is unfair and unjustified, emotional flashbacks can result in feelings of betrayal and cripple romantic relationships.

Nonetheless, one way to love your partner in the throes of a flashback is to remind yourself that their flashback is not about you, no matter how much they insist it is.

Despite that projection, if your partner is willing to cooperate, you can be helpful. For example, I’ve found that going over the protocol for flashbacks ahead of time, when my relationship partner is not in flashback, has helped her recognize my responses as an intent to support (rather than as a counter attack).

When I sense an emotional flashback in someone I love, I use these prompts.

Might you be having an emotional flashback?

I recommend using these exact words, so they recognize the question as part of a response protocol, rather than an accusation. One time, when a subordinate used this exact wording with me while I was on the verge of an all-out temper tantrum my response was, “Yes I am in an emotional flashback! And I’m not finished yet!”

We had a good laugh, the tension dissipated, and that was all it took to bring me out of it.

What are your feelings? Will you trying naming them?

Some people are so experienced at emotional suppression that they need to be reminded that they are having feelings. Denial of feelings will make the flashback worse, not better. When you prompt the flashbacker to recognize and name their feelings, you start the process of emotional self-expression that was denied them as a child.

Where in your body do you feel it?

An emotional flashback sometimes appears in a place that gives us a clue about the origins of the flashback.

“Frequently, physical illnesses are the body’s response to permanent disregard of its vital functions… (such as) the conflict between the things we feel and the things we think we ought to feel so as to comply with the moral norms and standards we internalized at a very early age.

“Experience has taught me that my own body is the source of all the vital information that has enabled me to achieve greater autonomy and self confidence.” — Alice Miller, The Body Never Lies (2006).

When in the past have you felt this way before?

After locating the trauma in the body, it may be possible to reconstruct experiences of previous flashbacks that trace a pattern all the way back to the original trauma. When a cognitive understanding of the trauma origins is achieved, the intensity of the feeling may subside, empowering flashbackers to reconstruct what Alice Miller calls “the true story of their own lives.”

Will you tell me about it?

This prompt is an invitation to listen to the flashbacker perform their reconstruction, without judging, contradicting, or arguing with their story. The most important thing about their narration of their own experience is practicing getting to a closer approximation of their truth. Because they’re talking about flashbacks, the story they narrate is not (yet) about the present moment trigger, but about the moments to which they flashback.

How might these flashback feelings have protected you and served you then?

Although we often think of strong feelings as the “problem,” the fact is that at some vulnerable moment in our past, emotional expression was an attempt to find a solution. It may be that an expression of anger or sadness that might have protected us from a dangerous situation in the past was prohibited or repressed in us, and that C-PTSD is the result of the repression. When we identify the problem that emotional self-expression might have solved, we begin the process of resolving the trauma by regaining control of our own emotional expression — rather than have our expression controlled by our parents, persecutors, or abusers for their own purposes.

Is the problem you had then the problem you want to be working on right now?

This prompt reminds the flashbacker that they have a choice. They are not victims of their own emotions in this present moment. That is, the freedom of emotional self expression that was denied them in the past (e.g., as a child) no longer constrains them today. When they decide what problem they want to be working on right now, they will be empowered to make faster progress towards resolution of that problem.

Is there a new solution to the old problem? Or do you choose a new problem?

Once the flashbacker realizes that an emotional flashback is an experience of past trauma in the present moment, they may be more willing to accept that they need a new solution to an old problem. That solution may not be obvious or attainable to them right away. Nonetheless, the recognition that new experiments are called for is an essential step towards breaking old, destructive patterns of behavior. The next step may be to brainstorm for new ideas about what they might try instead.

Patience

Although I’ve read accounts from Peter Levine and Michael Pollan (How to Change Your Mind, 2018) that describe a significant release of trauma in a single session of therapy, these accounts give insufficient description to the years of suffering, false starts, failed experiments, and hard work that led up to the breakthrough. My own journey, and those of whom I’m most familiar, has extended over five years of introspection, experimentation, rejection, and healing. Like a musical instrument, my sense is that mastering these steps will require deliberate practice, and that investment can result in something transcendent.