Everyone who has spent more than two days in a job has discovered that the description of and practice of their job are often two different things.

For example, in my job as a University professor, you might think my job is teaching, mentoring, and research. In fact, much of my job is filling out forms. Some days, several hours of my work day will be spent completing some damn form (incorrectly), and I hate it.

But what’s really awful is that the forms themselves are incomplete, obsolete, or sometimes, just ignored. At Arizona State University, we have forms that haven’t been updated in twenty years. Everyone just knows they’re obsolete, and nobody who knows any better even pays attention to them any more, but the Policy Handbook still requires them because no one ever bothered to revise a handbook that everyone knows not to pay attention to anyway.

The discrepancy drives me crazy.

Still, my frustrations are trivial in comparison to the difficulties faced by medical professionals. For example, medical errors are still the third leading cause of death in the United States (Makary & Daniel 2015).

And one of the leading causes of medical errors in the difference between the way their work is imagined and the way it is actually done (Blandford et al., 2014). Nobody imagines, at the time they’re performing some function, that they’re making a lethal error. They imagine that they’re doing their best to work around obstacles, within resource constraints, and under time and other production pressures.

Between work as imagined and work as done often lies danger.

A large scale industrial society needs predictable, repeatable, and reliable processes in its factories, job sites, and workplaces. Thus, standardization of processes and procedures are intended to conform work as done to what customers, mangers, and co-workers are expecting.

The problem is that the systems in which we perform work are complex, and that means they are subject to inconsistencies, randomness, and irreducible unpredictability. Workers intuitively understand that standard operating procedures (SOPs) are not suitable for every context (Catchpole & Alfred 2018). At the same time, productivity or performance pressures often incentivize workers to takes risks or short cuts that their experience has, for the most part, taught them will be fine — until they’re not.

Predictable, repeatable, reliable processes — in short, safe processes — will also fail to adapt, fail to innovate, and fail to afford opportunities to exercise the most precious technological resource: human creativity.

Work As Imagined in Entrepreneurship

The company I co-founded in 2018 is Morozko Forge. It makes the world’s first ice bath for whole body deliberate cold exposure. Because no one had every produced a product like ours before, we had to imagine the product before we could create it.

Imagination is the fountainhead of creativity, so entrepreneurial ventures could not exist without it.

The question that we, and every start up, are eventually confronted with is this:

How do we make our processes predictable, repeatable, and reliable, so that work as done conforms to work as imagined, when the work we imagine is always changing?

When our work fails to conform to our imagination, the result is defects, repair calls, rework, disappointed customers, and even safety hazards. On the other hand, if we did not allow our imagination to outstrip our work practices, we would never be able to innovate.

Some of our most important innovations have come from our mistakes and misunderstandings. Eliminating ALL of them may slow our innovation.

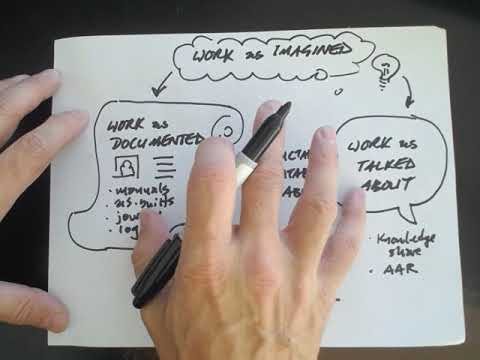

There are two processes that help bring Work As Done in closer conformance to Work As Imagined, without stifling creativity. The first is called Work as Talked About and the second is called Work As Documented.

Work As Talked About

The ultimate source of all business value for any entrepreneurial startup is the new knowledge they are creating, testing, putting into practice, and ultimately selling to customers.

In How Do You Know You Have Good Idea? I wrote about how successful, creative organizations like Pixar will test and improve the quality of ideas in conversations. Thus, one of the ways to close the gap between work as done and work as imagined, without crushing new ideas, is to subject our imaginations to multiple perspectives.

We have three conversational protocols to do just that: 1) What if… ? 2) Knowledge share, and 3) After Action Report.

What if… ?

One of the greatest strengths of any startup is how they Co-Creative Problem Solve (CCPS). This protocol is initiated by a companion who starts a sentence with “The problem is… “ to signal to their co-workers that they’re inviting a CCPS conversation.

For example, the Morozko Production Manager once invited me to CCPS by saying, “The problem is that the drain cock in the filter is leaking, and we’re scheduled to ship that ice bath tomorrow.”

When I’m accepting his invitation to CCPS, I respond with an idea like “What if we plugged the bulkhead unions to prevent the flow of water thru the filtration system, pulled the filter, and sealed the drain cock with permatex that we allowed to cure overnight?”

In the co-creative Protocol, it is his responsibility to describe the consequences of the idea before judging or expressing a preference for the idea.

Without the protocol, a worker might say, “Sure, I could do that!” And although the enthusiasm is welcome, the response truncates the co-creative problem-solving process. In other words, premature agreement runs the risk of missing a superior alternative.

In this case, the Production Manager responded, “If I (did that), we might fix the leak and ship on time, or we might discover that it doesn’t work and we wasted a whole day waiting for a non-solution to cure.”

Now that we understand the consequences of that alternative, we can continue brainstorming new alternatives until we settle on the alternative we prefer. Continuing to co-creative problem solve through three or more alternatives has often been the key to discovering what feels like genius-level solutions (rather than satisfying compromises).

To encourage co-creative problem solving, I remind my crew, “My first idea is rarely my best idea.”

As it turned out, the drain plug was missing a gasket. Installing the gasket fixed the leak, and the ice bath shipped when scheduled.

Knowledge Share

Because all startups are in the knowledge business, it behooves entrepreneurs to share knowledge when they discover it. There are three channels through which this is done:

Small group conversations. These are short, spontaneous, and focused. A standard procedure requires that the conversation continue until the parties have confirmed their understanding. For example, suppose one companion discovers a new way to repair flaws in varnish. Sharing the technique for that repair is best done in a one-on-one or small group demonstration. However, until the learners are able to confirm their understanding by repeating or replicating the knowledge to the satisfaction of the teacher, the knowledge transfer cannot be considered complete. Therefore, the teacher will not conclude a small group knowledge without the request, “Will you confirm your understanding?” at which point, the learners either repeat back or demonstrate the new knowledge. You might be surprised by the fact that it can take two or three attempts for both the teacher and the learner to agree on confirmation of understanding, which reinforces for us the importance of confirming the understanding.

Text Messaging. Whether using WhatsApp, Signal, or Slack, text messaging is a river of knowledge sharing. For example, Morozo Forge has channels called “R&D,” and “Shipping”, and “Production,” and one called “On the Road,” for posting updates while traveling. These are especially convenient for posting pictures and videos that initiate co-creative problem-solving protocols, coordinating work assignments, and posting improved technique or productivity hacks. Sometimes, they come in handy for documenting knowledge, too (see below). But messaging isn’t designed to be a repository so it’s clumsy as an archival record. Text messaging is better for extending the one-on-one and small group knowledge share over wider geographic and temporal spaces.

Large Group Meetings. Weekly Knowledge Share team meetings help distribute new knowledge throughout the company — whether people feel like it’s directly applicable to their job or not. I’ve heard others complain about how useless meetings are, and I wrote about it in 2 Things Critical to Organizational Communication. I think we all have the experience of tedious, time wasting meetings:

Critics of meetings like Gary Vaynerchuk fail to recognize that communication is what constitutes an organization.

Because the days of monopoly are over, every organization must compete on the basis of creativity and innovation because we live in an age when all business value is ultimately traceable back to knowledge. Creating, sharing, organizing, and monetizing that knowledge requires communication.

And face-to-face (F2F) meetings are still the highest quality, broadest bandwidth form of communication available.

— Thomas P Seager, PhD in 2 Things Critical to Organizational Communication.

After Action Report

Sometimes, we organize our Knowledge Share meetings in a format we call the After Action Report (AAR), because this format encourages us to revisit problems, solutions, or experiences that may have been resolved, but can still be improved upon. There are three prompts that make the AAR productive. They are: 1) What happened? 2) What did we do? 3) What could we do better?

These three prompts encourage us to share the knowledge of the experience, share the resolution, and improve the resolution. For example, one of our inspectors discovered water beneath the drain hole of an ice bath that was supposed to be packaged and shipped in hours. The water is typically indicative of a leak, and requires that packaging be stopped and a leak diagnosis protocol initiate, which is sure to delay shipment and disappoint a customer.

As the Production Manager was reviewing the leak diagnosis protocol with me, he broke his train of thought to ask, “What if the water wasn’t from a leak, but from a spill that took place before the deck was sealed?”

“If the water under the Forge was from a spill, rather than a leak, then we could package and ship with confidence and keep our commitments to our customer,” I replied.

We asked the craftsman who filled the ic bath and sealed the deck. Sure enough, he reported that there was a spill when he accidentally overfilled, prior to sealing the deck. The water was from that spill, not from a leak.

And there we found another example of the distance between Work As Done and Work As Imagined. Closing that gap improved productivity by allowing us to proceed with packaging and shipping immediately, and avoiding the delay of a fruitless leak diagnosis protocol.

The AAR protocol prompts review of the incident:

What happened was the inspector observed a puddle and halted the packaging process, which is what we want.

What we did was hold high level CCPS session to investigate how we missed a leak (that wasn’t a leak at all) and whether our leak diagnosis protocol was insufficient. That misallocation of executive energy is not what we want. Then, we asked a specific question of the craftsman that led to resolution of the issue.

What we could have done better sometimes requires a CCPS, and sometimes doesn’t. In this case, the Production Manager and the craftsman agreed to document (see below) spills on the production chart, so that inspectors have more information about the cause of puddles or other defects.

Work As Documented

In Rules vs Norms, I described how unstated organizational cultural expectations have a stronger influence on workplace behaviors than the written policies. This discrepancy between cultural and policy is one of the most important reasons that Work As Done can differ from Work As Imagined, and when the consequences are made clear by an accident or catastrophe, the unfortunate side-effect may be that workers who were operating in a way that is consistent with cultural become “blamed” for failing to adhere to the written policies that culture expectations were in conflict with the whole time.

Fire codes require that kitchen door on the floor of my University building must be open only when there is someone passing thru it. However, the occupants of my floor prop the kitchen door open.

Work as imagined by the building architect, the building inspector, and the fire safety marshal dictates that the door will close automatically, in exactly the way the door closer is designed and expected to do.

Work as done by the occupants props the door open to disable the automatic door closer, and thus overcomes the efforts of facilities staff to enforcing compliance with building codes.

Although the authority figures imagine compliance with rules, in practice the occupants have established a norm that is different from those rules.

- Thomas P Seager, PhD in Culture Beats Strategy: Rules vs Norms

In the case of the kitchen door, the fire codes provide documentation of Work As Imagined, and there is no documentation of Work As Done.

In any workplace, the distance between the two can be narrowed by either revising documentation to conform to our work practices, or revising our work practices to conform to our documentation. Because I don’t have the authority to revise fire codes, resolution of the case of the kitchen door would be to remove the doorstop that is used to prop the door open, conduct a knowledge share meeting, and post a label or sign on the door documenting the expectation that it remain closed. (The door already has an automatic closer installed).

Most of the time, we’re confronted with issues over which we have more authority than University fire codes. For example, when at Morozko Forge we discover that craftsmen have developed an ad hoc work around for when packaging isn’t cut to fit a products, we’re able to identify a packaging piece design issue. One resolution is to continue to order packaging materials that are custom cut to the wrong dimensions, train our craftsmen to ignore the instructions in our packaging manual, and teach one another the work-around technique because “everybody just knows” that’s how you’re supposed to do packaging.

These work-arounds are all too common in the workplace. On the one hand, they keep production moving along and they reward the ingenuity and creativity of the worker, who has the satisfaction of solving a problem that some designer (often remote from the actual work) created. On the other hand, they create a condition called decompensation (Woods & Branlatt 2011), in which the adaptive capacity of the organization is consumed by undocumented, unplanned, unproductive ad hoc “fixes” that make the production process more fragile to new disruptions.

What might happen if the craftsman who has invented and implemented the ad hoc work around technique for misfit packaging pieces calls in sick on a day when several ice baths are scheduled to be packaged? Without documentation, the craftsmen reassigned to packaging might not be able to access the knowledge of Work As Done that resides only in the expertise of the packaging craftsman. When the misfit is discovered, these craftsman will no doubt initiate a CCPS session to reinvent a resolution without the benefit of prior experience.

The result may be a colossal waste of energy that postpones shipment and disappoints customers. Far better would be to revise the documentation (such as the packaging manual, or the piece design) to conform Work As Documented to Work As Done.

There are three ways that we document or work: 1) Messaging, 2) Manuals, and 3) Personal Journals.

All three have proven productive. In the first case, we opened a new text channel solely for the purpose of documenting changes to design specifications, to make it easier to search for that documentation when performing work or revising Manuals. Texting is inferior to other repositories from the perspective of knowledge retrieval, but it requires so little effort on the part of the craftsmen on the production floor that the costs of documentation are very low.

Hard copy manuals (like comic books) are a superior source for knowledge retrieval, and allow craftsmen to post notes, make hard copy edits, or write other updates in the manual pages, without ever leaving the hardware world in which they work. The downside of Manuals is that they require a greater investment of effort to create. Thus, we’ll often download the pictures from text and assign manual revisions to a companion with weaker production skills, but stronger clerical/word processing skills.

Finally, we expect everyone at Morozko Forge to document knowledge in their personal journals. The act of writing it one their own pages, in their own hand, is often sufficient for them to retain the knowledge in working memory — or gives them a record to stimulate their memory during a Knowledge Share.

Balancing Creativity & Innovation with Reliability & Predictability

Every business organization must work with knowledge in two, incompatible modes at once.

Creation of new knowledge require exploration, in which creativity, imagination, failure, and reinvention are essential.

On the other hand, the knowledge discovered during exploration can only be made valuable when the organization has processes for exploitation of that knowledge, in which predictability, reliability, and repeatability are essential.

Exploration and exploitation are antagonistic goals, and navigating between them requires an almost schizophrenic ability to switch from one mindset to the other.

When organizations are preoccupied with exploitation, the distance between Work As Imagined and Work As Done may result in catastrophic consequences, because surprise is the opposite of predictable, repeatable, and reliable. However, when organizations are preoccupied with exploration we may find that they spend so much energy in Work As Imagined that they never get anything done.

Because of the emphasis on safety, so many organizations focus on conforming Work As Done to Work As Imagined, that they miss the potential innovations that are available in their own organizations. People are, by and large, conscientious and creative. They will discover problems and solutions in the course of their every day tasks, and in every organization there are informal processes for sharing those discoveries.

For example, back in the late 80’s when the fax machine and photocopier were essential pieces of office equipment, the documentation that came with these machines was understood to be useless. Fixing paper jams became the purview of countless, unsung office heroes who, through their own ingenuity and experience, had managed to master the machine.

Work As Talked About is one of these informal processes, and it can be effective for improving productivity of employees. However, the informal processes for sharing ingenious workarounds rarely scale well throughout the organization. To leverage the knowledge gains made by the people doing the work, it is also necessary to have effective processes for Work As Documented.

By strengthening both Work As Documented and Work As Talked About, the distance between Work As Done and Work As Imagined can be closed in way that both improve safety and reliability and exploit a continuous process of new knowledge creation throughout all levels of the organization.